TOP OF MIND: Protect the people from the virus and from the overreach of civil liberties

Technology in times of a pandemic can help, but how do we keep the data and the privacy of consumers safe? How can we protect the individual while we try to save the entire population?

Key take-away’s from this article:

Key take-away’s from this article:

- The same algorithms and AI technology used for terrorist and criminal surveillance measures are now being used to fight a pandemic

- Surveillance technology, biometrics, and Bluetooth tools are accelerating the practice of “contract tracing” which helps health authorities locate and contact people who may have interacted with an infected person

- Highlighted stories show that many citizens welcome the opportunity to participate for the betterment of their community and the world-at-large, but many do not trust that the government will erase the data and ease surveillance after the pandemic-threat

- Legitimate concerns have been risen, regarding long-lasting government overreach and enforcement measures

Digital sovereignty is an issue that is of particular interest to me, as is using technology for the betterment of the quality of life and societal advancement. I firmly believe that leaders should always rely on data for decision-making, while simultaneously, finding ways to protect and preserve each person’s digital sovereignty.

That is what makes the argument for tracking COVID-19 cases through cellphone data a compelling health and human rights conversation. On the one hand, we need to have accurate data to keep communities safe and help healthcare leaders make the right decisions to bend the curve of the pandemic and prevent future outbreaks. On the other hand, there are data protection organizations and human rights groups that argue that without legal tailoring of surveillance initiatives, governments may infringe on individuals’ privacy and overreach civil liberties.

The call-to-action is: For governments and health leaders to meet these issues in the middle with a clear and transparent approach that protects users’ privacy and data during the initial threat, and then effectively deactivates tracking and monitoring after the crisis. Among many critical questions, most importantly, what does ethics enforcement look like and who oversees individuals’ protections?

FULL SUMMARY: Link to the original article

COVID-19 presents an existential threat to humanity’s health, safety, and economic stability. There is an opportunity for technology and data to come together to help slow down the spread of the virus, and effectively support communications from leaders and healthcare workers. Countries like China, South Korea, Israel, and others within the European Union, are using algorithms and AI technology – that has in the past, been used for terrorist and criminal surveillance measures – to be repurposed for fighting the pandemic. The U.S. is in talks with private firms, Palantir Technologies, Inc. and Unacast, Inc., to develop tools to fight the pandemic.

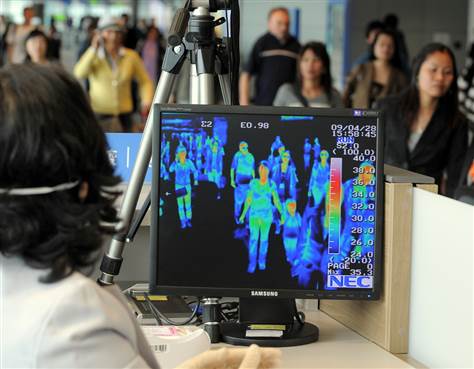

One of the most widely used developments is “contact tracing” — helping health authorities locate and contact people who may have interacted with an infected person. This can be an arduous and error-prone process without the aid of technology. Almost everyone agrees that there is a need for rapid response in containing and tracking the virus’ progress. An example of surveillance utilization is in China, where authorities use facial-recognition software and location tracking to identify people with fevers and direct them for testing, in addition to, keeping tabs on those who have been quarantined to ensure that they do not violate orders. The government is also using colored QR codes on mobile phones to show a person’s health status and contacts who have tested positive for COVID-19.

Other countries are making participation and tracking voluntary so that people feel that they have autonomy over the release of data.

Opening the door for surveillance and sensitive data-monitoring presents the opportunity for governments to overstep individuals’ civil liberties. “Any surveillance measures must have a legal basis, be narrowly tailored to meet a legitimate public health goal, and contain safeguards against abuse,” said a senior digital-rights researcher at Human Rights Watch, Deborah Brown.

Connectivity and access is a slippery slope for long-term tracking, posing questions around how boundaries are defined in the future and what is happening to the collected data (and how and where is stored), as well as security concerns for how data could possibly be hacked and misused by cybercriminals.

The fear of perpetuating the pandemic leads people to accept a “surveillance authoritarian society,” says civic activist Galileo Cheng. Like so many new and unpredictable changes that COVID-19 has ushered in, this is a challenge that sets a precedent moving forward for how we treat data and people’s digital sovereignty. It is only a matter of time before oversight committees and governing leaders will have to work together on how to build solutions around the global community’s best interest, as well as preserving and protecting autonomy.